The central feature of a suiseki art piece is a found object – a stone – that has been shaped entirely by Nature. So it’s understandable that, whenever suiseki lovers get together, the conversation almost always gets around to the issue of whether or not it is okay to cut a stone when making a suiseki.

There are different teachings and practices both here in the U.S. and in Japan (and much argument in both places). In my view it’s really an artistic decision rather than a matter of “okay” or “not okay”.

Some people come at the cutting issue from a conceptual point of view – they often express the feeling that cutting a stone damages the spirit of the stone. (Many people use the Japanese term kami, but the ancient Greek concept of a nymph probably serves just as well.) This is certainly in keeping with the historical roots of suiseki as objects which brought Nature indoors for Zen meditation and the Tea Ceremony. Suiban display is commonly used to express this feeling.

Other people are more concerned with the suiseki as a visual object. In this view, the artistic composition – the line, form, and visual balance – is the primary concern. For this group, it is acceptable to cut a stone if it improves the artistic composition – provided that it results in a good suiseki. Suiseki is treated more as Art in our modern sense, rather than seeing it through the lens of traditional spiritual belief. (See my earlier post on that topic.)

Neither point of view is “right” or “wrong”, and they aren’t even mutually exclusive. Some people emphasize the conceptual – and may be more forgiving of compositional “flaws” in uncut stones. The other group emphasizes the composition and is more forgiving of the human intrusion of cutting.

Here in Northern California, most people seem to follow the same practice as the Nippon Suiseki Association (see their FAQ here). We consider stone cutting to be acceptable – though good un-cut stones are more valued. There is however one significant difference between our practice and the Japanese practice.

For aesthetic reasons, the Japanese artists use various techniques (such as sandblasting) to modify the bottom face and edges of a cut stone so as to conceal the smooth face. In some cases additional work may even be done on the visible parts of the stone to modify the shape. This work is usually done very skillfully and is difficult to detect. (In the commercial world of course the seller should disclose this to you. I have a couple of Japanese suiseki, and I only found out later that they had been modified. However, they are beautiful stones and I enjoy them both.)

By contrast, our Northern California practice is to grind the sharp edges in order to make a good transition into the daiza, and no attempt is made to conceal the cut face itself. I am not aware of any Northern California artists (or commercial dealers) that make a practice of modifying the visible shape and people consider it to be improper and not part of the suiseki aesthetic.

Mas feels that the decision depends on the individual stone and what it needs. He will cut a stone, but only when the resulting suiseki will be very good.

Late Fall (shown in the photo below) is an fine example of a cut-stone suiseki. It is a classic mountain-shaped stone (山形 yamagata) that meets all the requirements of the rule of three-sides (三面の法 sanmen-no-hou). It has good asymmetrical balance, a well-defined straight peak, and the peak and both ends all come slightly forward towards the viewer (what is called good kamae 構). The stone material is good well-weathered serpentine, with a subdued deep brown color and interesting textures that enhance the lines of the stone, and is starting to show age and patina. This suiseki is currently in our entry way, and I enjoy seeing it every time I walk through.

“Late Fall”; W 16″ x D 7″ x H 6″; Clear Creek serpentine

< Previous | Home | Next >

Posted by Janet Roth

Posted by Janet Roth

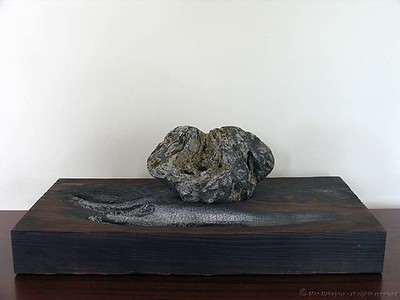

He made a daiza for this stone following the traditional style taught by California (and also Japanese) suiseki artists. A seat is carved into the wood to hold the base of the stone (this stone has not been cut, so the base is not flat), small uniform legs are made under the major visual masses, and the rim is flat all the way around. In this style, the daiza acts as a simple platform for the stone. The legs show just enough to visually support the weight of the stone, but otherwise are intended to almost disappear from the normal viewing angle (which is looking down slightly on the stone). The idea is to show the stone, the daiza itself is not considered important.

He made a daiza for this stone following the traditional style taught by California (and also Japanese) suiseki artists. A seat is carved into the wood to hold the base of the stone (this stone has not been cut, so the base is not flat), small uniform legs are made under the major visual masses, and the rim is flat all the way around. In this style, the daiza acts as a simple platform for the stone. The legs show just enough to visually support the weight of the stone, but otherwise are intended to almost disappear from the normal viewing angle (which is looking down slightly on the stone). The idea is to show the stone, the daiza itself is not considered important.

I found this stone on the Klamath River, and left it in the yard for over 10 years in the wind, rain, and sun. I was expecting that this process, known as youseki, would clean up the stains and show the beautiful white snowy mountain. But after 10 long years there was little color change – in particular the gray did not change to white. The years of youseki instead gave it a wabi-sabi and aware feeling. Wabi-sabi in suiseki is an antique and rusty look, and aware is a feeling of pathos, sorrow, misery, and wretchedness all combined. (These are very important ideas in Japanese art and do not translate to English very well).

I found this stone on the Klamath River, and left it in the yard for over 10 years in the wind, rain, and sun. I was expecting that this process, known as youseki, would clean up the stains and show the beautiful white snowy mountain. But after 10 long years there was little color change – in particular the gray did not change to white. The years of youseki instead gave it a wabi-sabi and aware feeling. Wabi-sabi in suiseki is an antique and rusty look, and aware is a feeling of pathos, sorrow, misery, and wretchedness all combined. (These are very important ideas in Japanese art and do not translate to English very well). the proportions and the grain seemed to complement the stone. I tried to position the stone very carefully, looking at the wood grain as well as the overall balance and composition. After setting the stone, I carved a deep hole and burned the wood with a blow torch. This is the first time in my suiseki art that I went beyond just staining and polishing the wood.

the proportions and the grain seemed to complement the stone. I tried to position the stone very carefully, looking at the wood grain as well as the overall balance and composition. After setting the stone, I carved a deep hole and burned the wood with a blow torch. This is the first time in my suiseki art that I went beyond just staining and polishing the wood.